Issue #20: The radical act of admitting you care

From casual situationships to quiet-quitting your job, when did it become cool not to try?

‘I wish I’d known it’s OK to be passionate and nerdy,’ said Greg James in an interview with The Times last year. When How To Fail host Elizabeth Day quoted the radio presenter’s words back to him in the introduction to a recent episode, I understood why that brief line had struck a particular chord with her – because it had with me, too.

In my mind, Greg was referring to that look of pure, bright-eyed passion that crosses someone’s face when they’re talking about a book or a hobby or a person they love; a look that makes them at once relatable (in their child-like vulnerability) but also exalted somehow, teleported to a place of hope and curiosity and courage, where trying your hardest is somehow less terrifying than the prospect of missing out entirely. He was referring to flow, the feeling that overtakes you when a task becomes so inherently compelling that the rest of the world – the potential for loneliness, the smallness of last weekend’s Oscars gossip – shrinks into irrelevance. He was referring to those little parts of ourselves we trim away, because they’re a little too earnest, too soft, too ostensibly try-hard for this world. And maybe I’m reading a lot, too much, into it – but you know what? So did Elizabeth Day.

In the past year alone, the ‘passionate and nerdy’ approach seems more passé than ever. It’s cross-generational, this not-caring business: Gen Z has, as writer Becky Meadows argues in a Medium piece, adopted ‘performative apathy’ as their defining trope, while Stylist diagnosed myself & my fellow Millennials with ‘What’s the point’ syndrome. The zeitgeist, as I perceive it, is for not-trying: in general life, in work and in love.

The world isn’t ending. Why are we still embracing Goblin Mode?

Last December, Goblin Mode – ‘a type of behaviour which is unapologetically self-indulgent, lazy, slovenly, or greedy’ – was named the Oxford University Press’ word of the year, and by a landslide public vote.

The appeal is clear. Goblin Mode is a natural continuation of the unkempt, dressing-gowned state many of us found ourselves in during the early stages of the pandemic, a reaction to work-from-home orders and the distant possibility that the apocalypse might, actually, be on its way. ‘Seemingly, it captured the prevailing mood of individuals who rejected the idea of returning to “normal life”,’ offered a representative for the OUP.

And yet – turns out the world is not (yet) ending, and we were able to acknowledge that, at least, after the first lockdown. Take, for instance, the backlash to Jess Glynne in 2020 when the singer publicly called out Sexy Fish – one of London Mayfair’s glitziest restaurants – for turning her away on account of the fact she turned up in a non-dress-code-abiding hoodie and trainers. Even in London, a nightlife scene where the dress code is worlds away from, say, the high-maintenance aesthetic of Liverpool, Jess was criticised. Sure, there was a discussion around privilege and her liberal use of the word ‘discrimination’, but on some level there seemed – back then – to remain a desire to uphold dress codes. Could it be that the successive lockdowns dealt us the final blow, cementing us all in a state of near-Goblin?

My two cents, as a working-from-home freelancer (meaning I could, quite easily, be the Goblinest Goblin of them all) is that Goblin Mode feels like an unnecessary pressure on my mental health, dragging me down to a perpetual ‘What’s the point’ state. Sure, I have my odd day channelling The Big Lebowski’s the Dude in my dressing gown – typically, coinciding with the writing of this newsletter – but the reality is, I don’t feel like myself after ‘giving up’ for a prolonged period of time.

Coming home to find my clothes on the floor make my mental space (messy at the best of times) spiral into overdrive; not getting dressed in the morning means I take myself, and my work, less seriously; eating in bed is overrated. I’m not saying I don’t do any of the above – it’s just, as far as aspirations go, I’d far rather uphold the Mrs Hinch era joy of tidying, or Marie Kondo’s zeal for folding, than romanticise the idea of checking out.

Quiet quitting

‘Quiet quitting’ was among Collins University’s defining words of last year, and it’s definitive of a larger, cultural movement towards shifting the work-life balance towards the latter. As Otegha Uwagba defined it in an episode of the Sentimental Garbage podcast, we’re living through ‘the antithesis of the Girl Boss…it’s no longer cool to be visibly working hard and hustling’.

I suspect there’s something of a tension between the implied extremity of the term ‘quiet quitting’ (which would imply little to no work at all) and its actual definition, which denotes something much more reasonable:

Quiet quitting: The practice of doing no more work than one is contractually obliged to do, esp. in order to spend more time on personal activities. - Collins Dictionary

In some sense, great. A laidback working culture was something I enjoyed about living in Lisbon last year: where, typically, people work to live rather than the reverse, and ‘What do you do?’ is all but banned as a conversational opener.

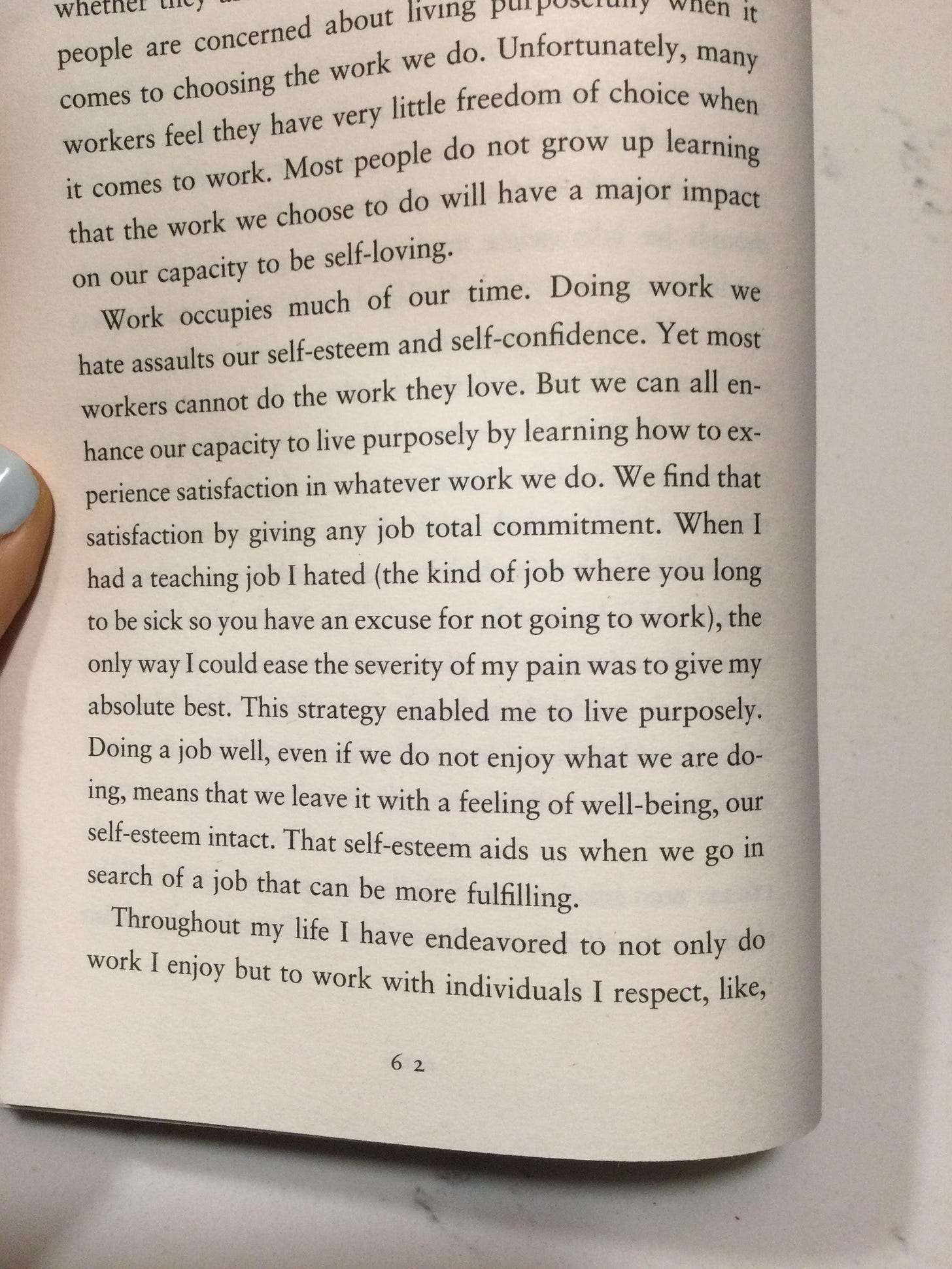

I wonder – and hope: is there scope to passionately, nerd-ily love what you do, even within those contracted hours (where we do, after all, spend the bulk of our waking hours)? Reading bell hook’s All About Love, I was drawn to the idea that investing effort in what we do – even if it’s not our dream job – is a means to support our self-esteem and even pave the way forward to a more fulfilling career step.

Casual situationships

Last, but not least, there’s love. While the concept of online dating fatigue is getting the due attention it deserves, what’s been lost amid this calling-out of ghosting, breadcrumbing, et. al is an appreciation for the full romantic spectrum of courtship, particularly the fun and hope of the early dating stages (why ‘woo’ someone who’s statistically only 50% likely to show up on your first date?).

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Shoulds by Francesca Specter to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.